By late January 1865, the death knell was tolling loudly for the Confederacy. It was a month after the fall of Savannah, Ga., the finale to Union Gen. William T. Sherman’s March to the Sea. On Jan. 21, as his army rested in Savannah, Sherman penned a letter to Gen. James H. Wilson, commander of the federal cavalry. Using his typically brash and cocksure language, Sherman congratulated Wilson and himself on the success of the march. “I Knocked daylight through Georgia, and in retreating to s[outh] like a sensible man I gathered up some plunder and walked into this beautiful City,” Sherman wrote, “whilst you & Thomas gave Hood & Forest (sic) a taste of what they have to Expect by trying to meddle with our Conquered Territory.”

The two Union generals were already preparing the second phase of their master plan: the Carolinas Campaign. Sherman would march north through North and South Carolina, while Wilson would sweep west across Alabama. They intended to combine forces with Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s armies in Virginia and finally face Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee in Petersburg, Va. But while the Confederates were still staggering from their losses in Georgia and might have felt the noose tightening, they didn’t plan on acquiescing to Sherman. They had a few final tricks in mind.

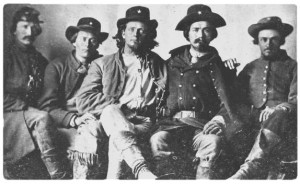

If the Confederates couldn’t defeat the Union armies head to head, they still could fall back on the sort of fast-moving cavalry tactics at which they had so often excelled. Rebel commanders ordered Capt. Alexander May Shannon to gather an elite group of 20 to 30 men from a crack Texas cavalry regiment to go on high-risk scouting missions around Sherman’s forces – if not to defeat them, then at least to slow and weaken them before they got to Grant.

The Eighth Texas Cavalry, better known as Terry’s Texas Rangers, was already revered by the Confederacy and vilified by the Union. The Rangers were often referred to as a “shock troop,” an outfit designed to lead stealth attacks. The regiment went on secret missions, often cloaked in blue overcoats, destroyed railway and telegraph lines, dipped behind enemy lines and gunned down Yankees at close range. They often led at the front and then covered the rear of the main force, the first and last line of offense and defense.

The Rangers were frequently given the dirty work other soldiers couldn’t stomach — and they didn’t take many prisoners. Confederate Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, often cited as one of the early founders of the Ku Klux Klan, once suggested that an outnumbered Union regiment surrender because “he had five hundred Texas Rangers he couldn’t control in a fight.”

Captain Shannon was the ideal commander to lead the Rangers’ scouting group, which was nicknamed “Shannon’s Scouts.” The 26-year-old was aggressive, shrewd and fearless. He also understood how to conduct covert reconnaissance assignments. Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood often sent Shannon and his scouts inside enemy lines, collecting intelligence and attacking Yankees caught ransacking Southern homes.

“Shannon’s Scouts” followed Sherman across Georgia and through the Carolinas in January 1865. They ran raids on his units and gathered valuable troop information. One of their main goals was to unhinge Sherman’s “bummers” — a nickname given to the general’s foraging teams that requisitioned food from Southern homes. They became notorious for looting and vandalizing. Shannon’s Scouts sought revenge.

Shannon was to attack any federal troops they encountered; if the scouts were overpowered and couldn’t retreat, they would separate and hide. They would even try to go on the offensive and capture any federal stragglers.

They were frequently outgunned and outnumbered, but astonishingly successful. They captured scores of Yankees; at one point a group of 15 guarded more than 100 Union prisoners. They would arm citizens with the prisoners’ weapons so the scouts could move on. Once, they even handed over guns to schoolboys and asked them to take the prisoners to Macon, Ga., which remained in rebel territory.

One scout, Robert Leander Dunman, later described how he and 17 others ran across a brigade of hundreds of federals. “We were quite as much surprised as they were,” Dunman wrote in a letter to his family, “but rather than let them discover our weakness in number, we began yelling and shooting as we came, making enough noise and bedlam for several times our number … they evidently thought the entire Confederate army was after them, for they started to run.”

As the Union thundered through the Carolinas, the Scouts became increasingly aggressive. Federal soldiers frequently accused Shannon’s Scouts of murdering prisoners after they had surrendered. General Sherman went into a fury when more than two dozen of his men were slaughtered, with a message left on their bodies. “It is officially reported to me that our foraging parties are murdered after capture and labeled ‘Death to all foragers,’” Sherman wrote in a letter to Confederate Gen. Wade Hampton. “One instance of a lieutenant and seven men near Chesterville; I have ordered a similar number of prisoners in our hands to be disposed of in like manner.”

General Hampton assured Sherman that if he dared execute any rebel prisoners that the Confederacy would kill twice as many federal men. Union Gen. Judson Kilpatrick blamed Shannon’s Scouts for the murders. Kilpatrick even offered $5,000 for Shannon’s capture, a reward that was never collected.

No one knows exactly how many soldiers Shannon’s men killed or captured, though he claimed his team assassinated almost 500 men during the March to the Sea.

When Lee surrendered to Grant on April 9, orders to surrender went out to all Confederate troops. But Shannon’s Scouts refused; instead, they scattered. Shannon himself stayed loyal to the Confederate government, and was assigned to escort the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, on his escape from Richmond, Va. Davis was caught before Shannon could reach him.

The war over, Shannon returned to Texas, where he became a successful businessman. He died in 1906 in Galveston, Tex.

Leave a Reply