LONDON — A crowd huddles around a towering pyre on a cold November night, waiting in anticipation. Out of the darkness, a figure steps forward with a blazing torch and ignites the pile, sending the crowd into a frenzy of ‘ooohs’ and ‘aaahs’ as the flames leap skyward. As they have for nearly 400 years, thousands of spectators watch the bonfire consume the effigy of a failed 17th-century terrorist.

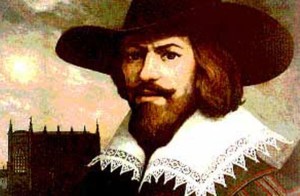

It’s Bonfire Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Day, annually and faithfully held in memory of the notorious conspirator who, along with a dozen other plotters, tried to blow up Parliament and King James I in 1605. As British traditions go, it’s a far cry from the nostalgic repertoire of royal pageantry, the ceremony of Parliament or the quaint black cabs and red double-decker buses of London. But every fifth of November, millions of Britons gather round bonfires — sometimes with a scarecrow figure representing Guy Fawkes at the very top — while fireworks crackle in the background. These days it’s little more than a family event, an excuse for a party.

For weeks in advance, children with stuffed dummies perched in wagons collect pennies for the ‘guy’ so they can buy candy and fireworks. The night has its origins in a fiendish underground plot that is far from the minds of young children collecting money around the neighborhood. Fawkes’s and his radical band of Roman Catholics (the practice of Catholicism at the time was illegal in Britain) planned to assassinate the king at his ceremonial opening of Parliament on Nov. 5, 1605, in protest over government persecution of Catholics.

In what is now known as the Gunpowder Plot, the conspirators hid 36 barrels of gunpowder in a vault directly below the House of Lords. They planned to blow up the king (who would have been in attendance with his wife the queen and son, his heir) and members of Parliament. An insider, however, blew the whistle on the plotters just two days before the king’s opening address. Fawkes, today sometimes portrayed as a roguish Robin Hood-type hero, was tortured and executed as a traitor. The present-day ritual may seem odd to outsiders, but over the centuries Britons have turned the event from the ritual burning of a traitor’s effigy into an autumn party.

‘I don’t think about Guy Fawkes when I think of Bonfire Night,’ said Richard Bacon, 20, a regular bonfire party-goer. ‘At Christmas I don’t necessarily think about Jesus Christ, but more about getting presents.’ ‘So that’s how I see Guy Fawkes Day — as an excuse to celebrate without having to think about it,’ Bacon said. There is no shortage of large-scale public bonfires, most of which are free of charge but do not allow alcohol. One of the largest pulls in a crowd of about 80,000 people every year. But although the number of private bonfires is declining, it’s not unusual to see families lighting their own fires in their back gardens. Sometimes these turn into huge parties where neighborhood groups organize the fire and a cookout in a resident’s back yard.

Nona Quested, who helps organize north London’s Finchley Road Bonfire Night Party, said the ritual has changed since she was a child after the war. ‘Guy Fawkes Day has lost a lot of its meaning since I was young,’ said 44-year-old Quested. ‘Now it’s just an excuse to have a party during the dreary winter.’ Although it is in decline, the tradition of children parading their scarecrow-like effigies and begging for ‘pennies for the guy’ has just about survived. ‘Remember, Remember the 5th of November,’ children chant as the big night approaches. ‘Gunpowder, Treason and Plot. I see no reason why gunpowder treason should ever be forgot.’

Like most parties, festive food is a part of the fun: roast potatoes cooked, appropriately enough, in the same fire as the unfortunate ‘guy, ‘ rock-hard ‘cinder’ toffee and parkin, a dense, sticky ginger cake. Not surprisingly, the partying also centers around explosions — the colorful type caused by thousands of fireworks at both public displays and private backyard parties. Only in strife-torn Northern Ireland is the sale of fireworks banned for fear that the gunpowder might be abused by modern-day plotters, but even in the rest of Britain there are calls to outlaw them because of the 1,500 injuries caused by fireworks every year. The tradition sustains a healthy seasonal business for fireworks makers, who estimate that 85 percent of their sales are made on the weekend before Bonfire Night. Dave Sayers, manager of Standard Fireworks, a small company in the northern town of Huddersfield, said Guy Fawkes Day means either champagne or bread and water. ‘All my business for the year will happen in the next two days,’ he said.

The rituals of Guy Fawkes Day reach from the back yards of the British public right up to the rarefied ceremony of government — tradition dictates that Queen Elizabeth II’s official opening of Parliament must not fall on the fateful date of Nov. 5. In addition, before the queen enters the Houses of Parliament, the royal Beefeater guards search the vaults below the House of Lords, armed only with lanterns, to be certain there is no hidden gunpowder. It is testimony to the popularity of Bonfire Night that even London’s trendy Time Out entertainment guide features appropriate clothing for Guy Fawkes Day, with a fashion designer choosing ‘scarves to keep you toasty on Bonfire Night.’